What Lessons can Apple PanAm and Polaroid Reveal?

What Lessons can Apple PanAm and Polaroid Reveal?

As companies grow many see sudden changes in the behaviour of their teams. The same people suddenly behave in very different ways, and it can be a mystery as to why.

As companies grow many see sudden changes in the behaviour of their teams. The same people suddenly behave in very different ways, and it can be a mystery as to why.

We as entrepreneurs often say that big companies are conservative and risk-averse, and the most exciting ideas come from small companies because entrepreneurs believe teams in small companies are the passionate risk-takers.

But I’m not so sure this is true. Because if you take a leader from a large conservative corporate, and transport them into a start-up, they’d be the first to support wild risky ideas, which might just transform the fortunes of the company.

So how can the same person act in a very risk-averse conservative way in one context and as a risk supporting entrepreneur in another?

Physicist and Nobel prize winner Phil Anderson (pictured) captured the core idea underlying the answer to this question when describing the flow of liquids, rigidity of solids, and the behaviours of electrons in a metal. Saying. “The whole becomes not only more than but very different from the sum of its parts”.

Physicist and Nobel prize winner Phil Anderson (pictured) captured the core idea underlying the answer to this question when describing the flow of liquids, rigidity of solids, and the behaviours of electrons in a metal. Saying. “The whole becomes not only more than but very different from the sum of its parts”.

If we drop a molecule of water onto a block of ice it freezes. But if we drop the same molecule of water into a pool of water, it simply slushes around with the other molecules.

This change is the result of two competing forces, and when people organise into a team with a mission, they also create two competing forces. Let’s call them ‘reward’ and ‘title’.

When the team is small, everyone’s ‘reward’ for a successful outcome is high.

At a small technical company developing a new product that will replace mobile technology and revolutionise the way people interact with each other. If the new product works and is adopted by the mass market, everyone will be a hero and probably a millionaire.

If it fails, everyone will be looking for a job. In this instance, the perks of a ‘title’ or the increase in salary from being promoted are small in comparison to the high stakes of product success or failure.

As teams and companies grow larger the potential ‘reward’ in outcomes decrease, while the perks of a ‘title’ increase. When the two cross, pressure builds and the system starts to fail, and incentives can begin encouraging behaviour no one wants.

The same teams – with the same people – begin ignoring riskier projects with high potential ‘reward’ for conservative risk-free projects with little or no reward to maintain their ‘title’.

The bad news is – as companies grow – these situations are inevitable. All liquid freezes.

The good news – if we understand the forces behind this happening – we can do something about it.

Water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit, and on snowy days we throw salt/grit onto our pavements to lower the temperature at which the water freezes.

We do this, as we want the snow to melt rather than harden into ice, instead of forming wet puddles we can walk through, rather than have us slip on the ice and hurt ourselves.

The same principle can be used to engineer more innovation in organisations, by identifying small changes in structure (rather than culture) that can transform a rigid team.

History is littered with business leaders focused on the next big thing to make history, rather than looking at how the market is changing and making continuous small changes to the products they’ve already got to best service the continually changing market.

PanAm Mistakes

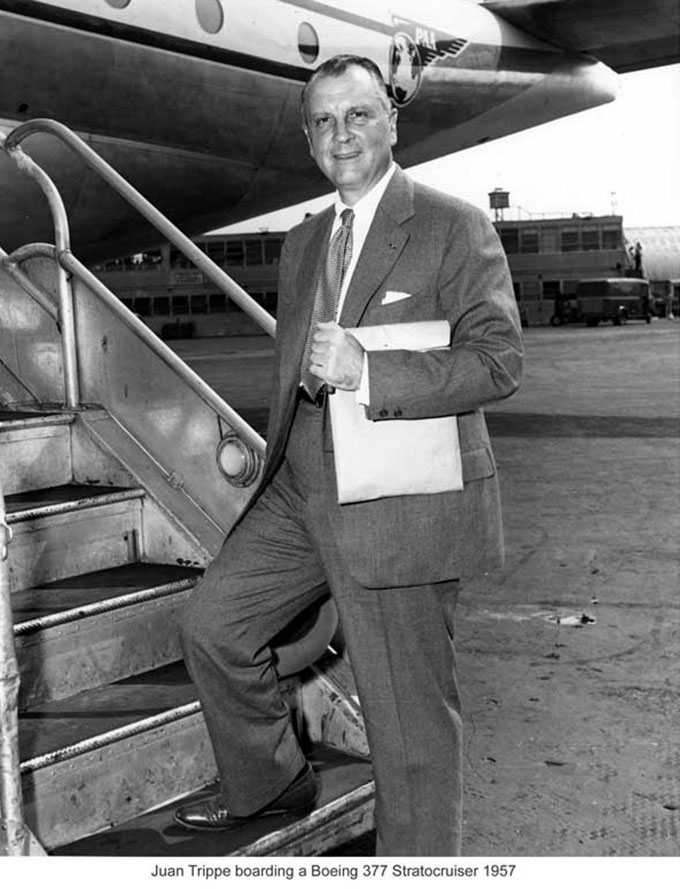

Pan Am founder Juan Trippe (pictured) is a great example. Trippe built Pan Am into the world’s biggest airline by taking huge risks with giant leaps in technological advancements. Unfortunately, his last (and probably biggest) leap eventually brought the company to its knees.

Pan Am founder Juan Trippe (pictured) is a great example. Trippe built Pan Am into the world’s biggest airline by taking huge risks with giant leaps in technological advancements. Unfortunately, his last (and probably biggest) leap eventually brought the company to its knees.

Trippe was so focused on the next big thing he ignored impending changes in the commercial aviation market. The US government were being lobbied by smaller airlines because Pan Am was acting as a cartel, which led to an investigation. At the same time, some other airlines made small changes to their product and business model, by moving to secondary airports and operating hubs and spokes with fast turnaround times. Which provided a better and cheaper service to consumers.

These factors led to Pan Am losing market share, yet, Trippe still went ahead with his biggest and final leap, asking Boeing to build him a plane to carry 2.5 times more people. Boeing agreed, calling it the 747, and Trippe ordered 25 at a cost of $525 million back in 1965.

This was a fatal mistake as you also need 2.5 times more customers to fill these planes, at a time when Pan Am was losing customers to other airlines who had made small changes to their business model, which had a big impact on price and service.

Trippe had failed to see he needed to make small changes to his existing business model too, rather than try and take a giant leap this time. Following this Pan Am spent to next 20 years lurching from one crisis to another and finally closing its doors in 1991.

Polaroid Snaps

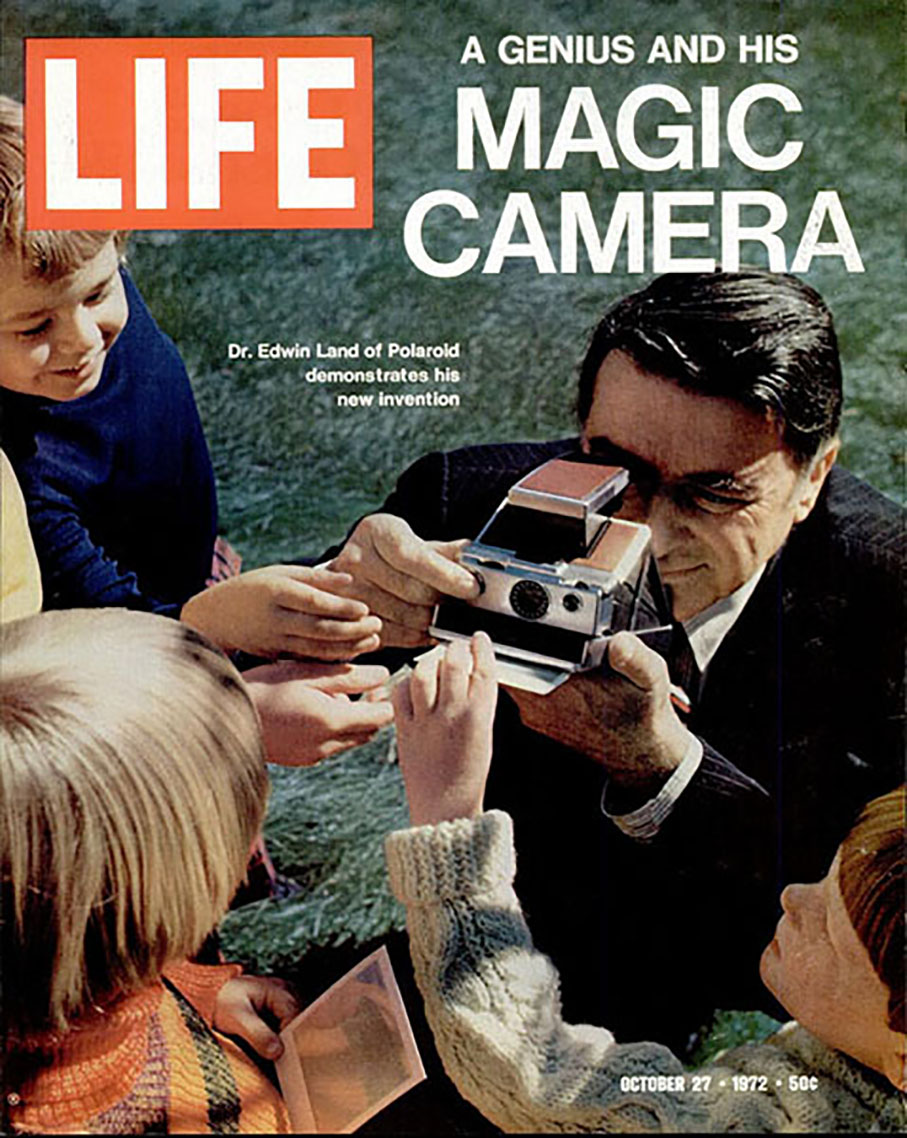

It was a similar story for Polaroid and their CEO Edwin Land. Land (pictured on the cover of Life magazine holding his new invention) increased Polaroid’s revenues from $1.5 million in 1948 to $1.4 billion in 1978 through a series of gigantic leaps in technology.

It was a similar story for Polaroid and their CEO Edwin Land. Land (pictured on the cover of Life magazine holding his new invention) increased Polaroid’s revenues from $1.5 million in 1948 to $1.4 billion in 1978 through a series of gigantic leaps in technology.

In the ’70s, Land was advising the US Government and helped build the world’s first digital satellite, which was able to beam back live digital photos from space and allowed the US to look at events around the world as they happened.

And the mystery is why Land didn’t build on this digital technology, as it was way before Sony, Canon and Nikon had even begun to work on digital photography.

Instead, Land went once again for a gigantic (which was to be his last) leap, by spending $200 million developing a high-quality film recording and playback device called ‘Polavision’. Don’t get me wrong, for the time (1978), the product was amazing. But Land had failed to grasp consumers didn’t need such a high-quality device, and certainly not at the lofty price of $3,000 in today’s money.

Land had bet the company on Polavision being a success and had already built 200,000 units in a new factory they’d set up. By 1979 most of the units remained unsold and they were written off as a loss. Polaroid shut down Polavision and Edwin Land resigned, sold his shares, and cut all ties.

During this time Sony, Canon and Nikon had been making small changes to their existing products and business model, one of which was digital photography. If only Land had done the same.

So, can a business leader hell-bent on only creating gigantic leaps in technology change and also adopt the strategy of small advancements on their existing products and business model?

Hell yes, and probably the most high-profile person to prove this point is Steve Jobs.

Taking a Bite from Apple

Jobs (pictured) was forced out of Apple in 1985 after the failure of his giant leap project the ‘Macintosh’. And by all accounts he only had time for employees directly involved with his giant leap projects, calling them ‘artists’, and referring to the others working on their earlier products as ‘bozos’.

Jobs (pictured) was forced out of Apple in 1985 after the failure of his giant leap project the ‘Macintosh’. And by all accounts he only had time for employees directly involved with his giant leap projects, calling them ‘artists’, and referring to the others working on their earlier products as ‘bozos’.

A similar thing happened when Jobs bought NeXT and built a supercomputer called the ‘NeXT Cube’, saying at the launch “I think together we’re going to experience one of those times that occurs only once or twice a decade in computing.”

NeXT then announced a partnership with Businessland (the largest computer retailer in the U.S.), predicting $150 million in sales within the first 12 months.

The ‘NeXT Cube’ was a beautiful, technologically remarkable, and wildly expensive machine. But competitors (though not as powerful) offered more convenience, more useful applications, and lower costs.

Jobs had designed his factory for billions of dollars in sales, but over the course of the next year, Businessland only sold 400 NeXT Cubes. The following year Businessland ceased to exist, and NeXT teetered with bankruptcy until Jobs returned to Apple and convinced the board to buy them.

It was before Jobs returned to Apple where he changed and learned you can operate two growth strategies simultaneously. Small advances in existing products and gigantic leaps in technology.

In 1986 Jobs bought the computer graphics division off Lucasfilm and renamed it Pixar Inc. Pixar had developed their own supercomputer which they used to render animation films for the likes of Disney, and Jobs wanted to commercialise the technology and sell it to businesses.

Much like happened at NeXT it was a flop and Jobs spent much of the following decade keeping bankruptcy at bay by using his own money to keep Pixar afloat.

It wasn’t until Jobs brought in Lawrence Levy things began to change. Lawrence worked with the existing Pixar team and found they had a fantastic existing product ‘digital animated film making’.

The rest is history and Jobs learnt you can build on existing products to become successful, and that together with gigantic leaps in technology you can create a fantastic business.

When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, Apple had a conventional structure for a company of its size. General managers ran products, or “business units,” each with their own bottom lines. And like in many large companies, those general managers often worked against each other, leading Apple to the brink of bankruptcy.

Through what Jobs had learned at Pixar and believing that conventional management had stifled innovation (in his first year returning as CEO) Jobs laid off the general managers of all the business units, put the entire company under one P&L, and combined the disparate functional departments of the business units into one functioning organisation.”

In other words, Jobs single-handedly destroyed the silos that were killing Apple, forcing the entire company to work together as a single and cohesive unit, embracing both ‘reward’ and ‘title’ teams.

Darren Turner’s imaging business success story began in 2003 when he opened a retail store in the UK selling printer supplies to home users & small organisations. Since then he has moved into a business unit, grown his team and continued to adapt to match his customers’ changing needs. He has developed a ‘fit for purpose’ office products and solutions business model that provides certainty of cost and service for small businesses, charities and schools—thus providing them complete peace of mind.

Darren Turner’s imaging business success story began in 2003 when he opened a retail store in the UK selling printer supplies to home users & small organisations. Since then he has moved into a business unit, grown his team and continued to adapt to match his customers’ changing needs. He has developed a ‘fit for purpose’ office products and solutions business model that provides certainty of cost and service for small businesses, charities and schools—thus providing them complete peace of mind.

He has become a trusted advisor for small organisations across the world. Turner invites you to chat with him about your business, reaching out to him on LinkedIn, email or on the phone at +44-7887-548523. Especially on this topic: “What Lessons can Apple PanAm and Polaroid Reveal?”

Read his other posts and blogs:

- What Lessons can Apple PanAm and Polaroid Reveal?

- Who Will We Sell To When the Machines Take Over?

- How the Rolling Stones Found their Satisfaction

- Shake Up Your World the Murakami Way

- Lead your Team like Genghis Khan: an 11-step guide

- Growing Your Business Like Post-war America

- The Matteo Ricci Strategy to Find Middle Ground

- Giving the Shirt Off Your Back for Quality Price and Ethics

- Good Business Needs Good Writers Too

- Butterflies Bumblebees and Shapeless Boxing

- The Martial Art of Fighting for your Business

- Walking the Plank with Pirates

- Resilience is Knowing When Not to Quit

- My View on the Future of the Print Technology Industry

- Planes Trains and Automobiles (and bicycles)

- Why Procrastinate Today When You Can Put it off Until Tomorrow

- Planting Trees as an Office Solution

Please add your comments below about Darren’s post, “What Lessons can Apple PanAm and Polaroid Reveal?” or go to LinkedIn and join the social media conversation.

Leave a Comment

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!